Organisational Design Part 6: Composing in Motion to Replace Yesterday

Organisational Design is the second of sixteen chapters in StartUp Space, and it guides entrepreneurs through managing company growth from inception to maturity.

StartUp Space is an entrepreneur's need-to-know guidebook that helps entrepreneurs start and run a business by visualising its structure and information flows.

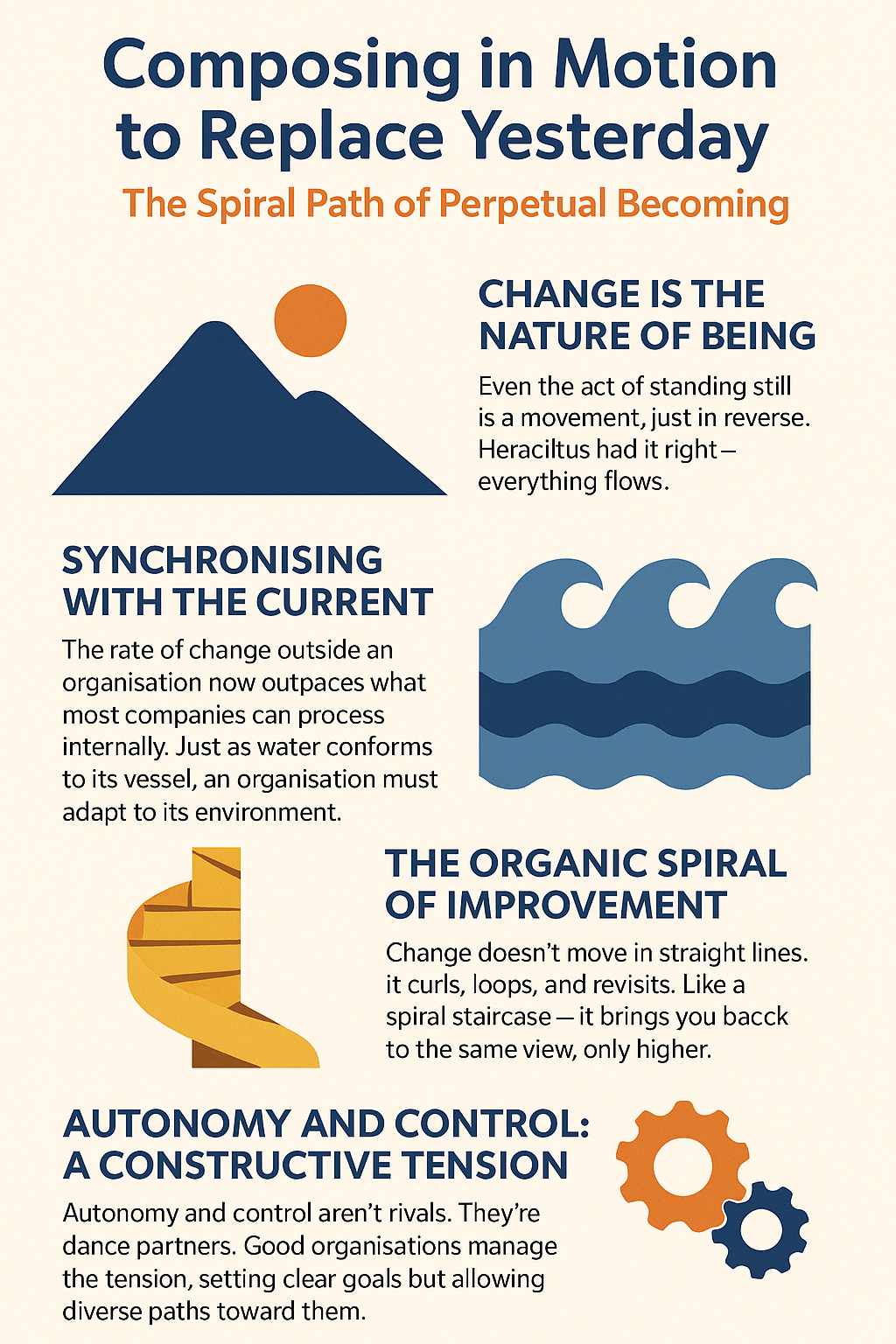

The Spiral Path of Perpetual Becoming

Change isn’t a strategic choice—it’s the nature of being.

Even the act of standing still is a movement, just in reverse.

The idea of standing still is a fiction. Nature doesn’t permit stasis. Even a seemingly immutable stone is bustling with the whirling of invisible electrons. You may sit still, but the world doesn’t. It drifts forward—and takes everything else with it.

Once perceptive, your relevance begins to blur, and your knowledge, once fresh, starts to lose its edge.

The world outgrows you.

Heraclitus had it right—everything flows.

So, you can try not to change. But what you’re doing is fading. It's the only exit that's left.

In less poetic terms, when we stop changing, we cease to matter.

Even if you're on the right track, inertia makes you a sitting duck. Movement is required, even if it's careful.

The modern business world doesn’t so much march forward as it swirls. Technologies shift, markets rearrange themselves, and consumers develop expectations that didn’t exist a quarter ago.

Staying still is no longer risky—it’s fatal.

To endure, a business must become less like a marble monument and more like water. Not because water is soft, but because it’s adaptable. It adapts, and in doing so, outlasts.

As Bruce Lee said: water becomes the cup, the bottle, the teapot. It yields, but only to reshape.

So, change management isn't a single announcement or some slick rebranding campaign. It’s the daily, sometimes uncomfortable art of enabling people and systems to stay in motion without falling apart.

Synchronising with the Current

The rate of change outside the organisation now outpaces what most companies can process internally. And yet, that pace isn’t going to slow. It will increase the speed.

Just as water conforms to the vessel it inhabits, an organisation must adapt to its environment. This isn't about reacting in panic but designing for fluidity. A company’s shape—its culture, structure, workflows—shouldn’t be cast in iron. What made sense yesterday might unobtrusively become a bottleneck tomorrow.

A wise organisation questions its assumptions—not out of self-doubt, but of respect for reality.

Like a snake shedding its skin, a business must regularly discard what no longer fits. It’s not loss—it’s necessary for growth.

The Sacred Cow on the Shifting Ground

Nothing inside a business should be above examination. Not your process maps, not your reporting lines, not your workflows. The only sacred ground is your core philosophy—your reason for existing. That’s the heartbeat. Everything else is fair game.

Culture isn’t a museum piece, and neither is structure. Both are tools meant to be sharpened or replaced when dull.

Listen to where the gears grind. Where do systems groan? Where do employees hesitate? Where do clients wince?

Change often displays itself not as a marching band but as a whisper.

The leader's job is to listen.

Start small. Fix the noise. One thing leads to another. You notice a few loose bolts in the system, and then a few in yourself. That’s the sign you’re doing it right.

The Organic Spiral of Improvement

Forget ladders and leaps. Change doesn’t move in straight lines. It curls, loops, and revisits. Like a spiral staircase—it brings you back to the same view, only higher.

At first, the cycle feels epic. You revamp your structure, retrain teams, and re-declare your mission. You reach the end and feel… triumphant. And then you notice something in the foundation needs reworking.

Welcome to loop two.

What was a final product now feels like a prototype. But that’s not a step back—it’s progress. You’re seeing with more perceptive eyes.

Every ascent on the spiral refines the company and its people. Language sharpens, vision focuses, and leadership matures.

The alternative spiral, of course, is the one Dante described—each level of stagnation more punishing than the last. Botticelli captured the descent as a funnel of horror. It’s not just a hellish metaphor—it’s what happens when we stop evolving.

As Drucker once hinted, clinging to yesterday’s logic is often more dangerous than any external chaos.

The Spiral as Habit, Not Crisis

Big, dramatic overhauls are rarely as effective as they seem. They exhaust people, unsettle continuity, and make heroes out of firefighters, not builders.

Consider change as rhythm—regular, modest, intentional—an hourglass, not a thunderclap.

This isn’t a call for perfectionism. It’s about building a culture that assumes nothing is ever done perfectly. "Never good enough" isn’t a complaint—it’s curiosity with standards.

Every day, the organisation that improves a little becomes immune to stagnation without becoming addicted to reinvention.

Autonomy and Control: A Constructive Tension

Autonomy and control don’t naturally align. One values freedom, the other, order. But in healthy organisations, they’re not rivals. They’re dance partners.

Autonomy allows people to think, care, and try something new without asking permission. It's a vote of confidence in competence.

However, autonomy without direction quickly devolves into disarray. Everyone does what they think is best, and those things often clash.

Control, on the other hand, ensures alignment. It prevents drift, saying: this is where we’re going. But too much of it stiffens the joints. People stop trying. Or thinking.

Good organisations don’t choose between the two. They manage the tension. They set clear goals but allow diverse paths toward them.

When autonomy and control work in collaboration, innovation feels secure. And accountability, rather than feeling like a trap, becomes a shared responsibility.

Freedom’s Twin: Accountability

Autonomy without accountability is a teenager’s dream. But in organisations, it’s a short path to dysfunction.

If people are free to act, they must also be responsible for outcomes. Not in a punitive sense, but in the spirit of ownership.

Ambiguity around responsibility breeds confusion. People step on each other’s toes—or worse, step back entirely, since no one knows who is meant to do what, and as a result, no one does much at all.

Accountability brings form to freedom, turning potential into performance.

When people understand the borders of their role and what lies within them, they step up, and the company breathes easier.

Contextual Leadership

Not all roles require the same balance between autonomy and control. A sales executive navigating the needs of moody clients requires flexibility, while a payroll clerk, ideally, should not.

Some people need leeway, while others need a checklist. The trick is knowing which is which.

This is the varied art of leadership—not to impose uniformity, but to distribute discretion appropriately. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work. Instead, distribute trust like oxygen—where it's needed most.

And when delegation goes wrong, real leaders don’t deflect. They own the choice. After all, delegation doesn’t remove responsibility—it extends it.

Change management is ultimately self-management. It's the organisational version of growing up. It’s about accepting that fear, friction, and fatigue are part of the deal—but so are growth, reinvention, and, occasionally, brilliance.

In a world that doesn’t stand still, standing still is the one decision that guarantees you’ll fall behind.

The next chapter of StartUp Space, Organisational Design Part 7, is about Creativity and will be published next: Creativity is just connecting things

The previous article in the Renaissance 2.0 series is: Architecture of Power

If you found this post interesting, please consider restacking it and sharing it with your audience.

You will guide my writing in the future if you share your thoughts in the comments